Lets Talk About “Core Stability” for athletes

What is it & how does it make you perform better?

By Britt Caling, APA Sports Titled and Australian Olympic Team Physio, 2016

While Elite Athletes are constantly aiming for improved performances, this motivation is also found in age-group, masters and social athletes of all levels and across all sports – I dare you to disagree!

There are many factors that need consideration if you want to improve your Sports Performance: – improving your skill of performance (whether that be run technique or efficiency, cycle, swim, paddle technique etc),- remaining uninjured and illness-free so you can train consistently over a period of time. This in turn requires finding the ‘sweet spot’ of training volume and the right variations of training load- increasing all components of your “fitness”, that is, speed, power, agility, flexibility, balance, strength and “core stability”. This is usually achieved via strength and conditioning (S&C) gym-based programs or home exercises.Core Stability exercises are invariably included in programs to make athletes better/faster/stronger.

But what really is “Core Stability”? And does it actually help you perform better?

The concept of our ‘Core’ means different things to different coaches, trainers, health professionals and even researchers. Much of the gym industry presents the image of our ‘core’ being our abs, with the idea that doing lots of crunches and abdominal bridge/plank holds will improve our ‘core stability’. This is a very limited view, and in fact, in some cases may be detrimental to sports performance if it creates patterns of bracing, breath holding and other movement patterns that are not specific to your athletic pursuits.

The original concept of core stability was actually morphed from an idea of spinal stability represented by the work of Panjabi in 1992 and then later Jull, Richardson & Hodges from the University of Qld. Panjabi was a mechanical engineer and biomechanist from Yale University who analysed how the spine moved using Cadavers. His work proposed that the lumbar spine (low back) was stabilised in neutral positions by the interaction of passive elements (such as joints and ligaments that join bone to bone), active elements (muscles and tendons that connect muscle to bone) and neural elements (our Brain and nervous system control of the muscles).

The original concept of core stability was actually morphed from an idea of spinal stability represented by the work of Panjabi in 1992 and then later Jull, Richardson & Hodges from the University of Qld. Panjabi was a mechanical engineer and biomechanist from Yale University who analysed how the spine moved using Cadavers. His work proposed that the lumbar spine (low back) was stabilised in neutral positions by the interaction of passive elements (such as joints and ligaments that join bone to bone), active elements (muscles and tendons that connect muscle to bone) and neural elements (our Brain and nervous system control of the muscles).

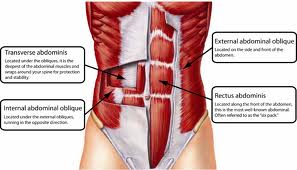

Within the elite sport strength and conditioning profession, the ‘core’ is typically referred to as any musculoskeletal structure that is encompassed by the abdominal and lumbar spine regions (including the transversus abdominis {deepest abdominal layer}, internal and external obliques, rectus abdominis, quadratus lumborum back muscle, multifidus deep small back muscle, gluteus medius and maximus, pelvic fioor muscles, and the diaphragm). An athlete’s ability to contract these muscles and stabilise joints during movement – as well as limit unwanted movement – is referred to as control and stability.

Elite S & C coaches will tend to focus on contraction and  connection of the limbs to this ‘core’ to improve movement efficiency and therefore sports performance. The definition of Core Stability that I believe relates well to sports performance is that given by Kibler and colleagues in 2006: which is ‘the ability to control the position and motion of the trunk over the pelvis and leg to allow optimum production, transfer and control of force and motion to the terminal segment’. If we therefore consider that ‘Core Stability’ is the ability to position and use the torso, trunk and pelvis as a stable base so that the arms and legs can efficiently produce force to move and propel us, then we should be able to understand that improving our ‘core stability’ should make us more efficient athletes and help us perform better. Better ‘core stability’ should allow us to produce more force at the end of our limbs, ie to push harder into the ground when we run which will propel us forwards better, or allow us press better on the water when we swim, and have less wasted energy (ie less loss of force transfer from our body positioning our paddle in the water to the propulsion forwards by pressing the paddle against the water, or less sideways movement of our pelvis on our bike saddle means more force to push into the bike pedal to again propel us forwards faster).

connection of the limbs to this ‘core’ to improve movement efficiency and therefore sports performance. The definition of Core Stability that I believe relates well to sports performance is that given by Kibler and colleagues in 2006: which is ‘the ability to control the position and motion of the trunk over the pelvis and leg to allow optimum production, transfer and control of force and motion to the terminal segment’. If we therefore consider that ‘Core Stability’ is the ability to position and use the torso, trunk and pelvis as a stable base so that the arms and legs can efficiently produce force to move and propel us, then we should be able to understand that improving our ‘core stability’ should make us more efficient athletes and help us perform better. Better ‘core stability’ should allow us to produce more force at the end of our limbs, ie to push harder into the ground when we run which will propel us forwards better, or allow us press better on the water when we swim, and have less wasted energy (ie less loss of force transfer from our body positioning our paddle in the water to the propulsion forwards by pressing the paddle against the water, or less sideways movement of our pelvis on our bike saddle means more force to push into the bike pedal to again propel us forwards faster).

Given this understanding, we need to move away from the concept of using a generic set of exercises (such as abdominal plank/bridge holds or fit ball balance exercises) to improve core stability and sports performance. Core stability exercise programs for athletes need to focus on:

– Improving body proprioception- understanding how and where to position parts of the body for optimal force production and muscle recruitment, and understanding how to reduce the effort used in movement (note how the best athletes in their sport always make what they do seem “easy”),

– Improving the ability to maintain a good, and stable, position of torso, trunk and pelvis with different movements of the limbs – Developing ‘reactive’ stability of the athlete. That is, the ability of the body to react to unexpected forces without using excess/unwanted muscle contractions and movements.

– Being specific to the athlete’s sport, or weaknesses of the athlete, in relation to the sports skill.

The research tells us that only core stability exercise programs that are really specific to the demands of the sport will produce performance improvements. While completing a series of abdominal crunches and fit ball  balance exercises has been shown to improve the ability to do crunches and balance on a fit ball (plus give you nice hard-toned ab muscles), this alone does not translate to racing or performing better/faster/stronger in your sport. As an example, a cyclist aiming to improve their time-trail performance would be better performing deep lunging-based exercises, with progression to split jump exercises, where they focus on maintaining good pelvis and trunk position rather than doing squats on a fit-ball.

balance exercises has been shown to improve the ability to do crunches and balance on a fit ball (plus give you nice hard-toned ab muscles), this alone does not translate to racing or performing better/faster/stronger in your sport. As an example, a cyclist aiming to improve their time-trail performance would be better performing deep lunging-based exercises, with progression to split jump exercises, where they focus on maintaining good pelvis and trunk position rather than doing squats on a fit-ball.

So the next time you are doing your “core stability” exercises, consider how specific they are to the technique and skill requirements of your sport. Ask yourself what your racing, competition or sports performance weaknesses are and then talk to a strength and conditioning coach, a trainer, or a sports physio that understands your sport. Don’t waste time doing a core stability exercise program that is not going to ultimately help improve your sports performance.

Britt xx